“We need a food bank.”

Those five words, noted casually in the minutes of numerous meetings in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, stuck with me even after the emergency declarations ended.

With great anxiety, I remember the first of these meetings, sitting in the conference room of the Garrett County Health Department in far Western Maryland, nestled atop the Appalachian Mountains. What remained of our Management Team, those willing and able to come into the building as the state began sending workers home, made final preparations before our offices would be shuttered to most in-person services for months.

At a time of great fear and concern, we weighed topics that became the foundation of our ethics policy for our PHAB (Public Health Accreditation Board) reaccreditation. These were the first of many decisions that were made during an event that hit our small, rural community especially hard.

While I remember little about the words spoken during this long planning session, I recall two things:

- Our infectious disease nurse whipping together a batch of hand sanitizer in the upstairs men’s room sink with miscellaneous alcohol and the biggest jug of aloe I’ve ever seen, and…

- The moment that it was decided that enforcement and regulation were more important than our neighbors’ hunger.

While Maryland has a highly centralized food bank system (Maryland Food Bank) that is incredibly well-funded and does a good job of meeting the needs of the majority of the state, Western Maryland has long been left behind.

This theme is not uncommon and defines most of my lived experiences in the Appalachian panhandle of one of the country’s most urban states. Just hours away from our nation’s capital is an entirely different world, not marked by our struggles but defined by our resilience.

When I tell people that I work in Maryland, I’m often asked about Washington, D.C. (which is known only as Wa”r”shington, with our intrusive Appalachian Rs), my feelings about crabs and Old Bay (by folks who’ve never experienced the trauma of skinning a deer at the age of four), robust public transportation (although we’re still holding out hope for sidewalks that extend beyond a few hundred yards of the county seat), and what life is like living at Deep Creek Lake (a premier destination across the mid-Atlantic, known for exuberance, wealth, and luxury).

In the face of these statements, my colleagues and I often laugh. While our boundaries, despite many attempts by politicians, remain within the frame of Maryland, our culture, people, and health outcomes more closely match West Virginia, the state that encompasses more of our border than Maryland itself.

As I sat in a room full of rather kind folks with MPH, MA, MS, and acronyms galore after their names, I reflected on how different I still was from many of my counterparts. Despite our shared regional origins, we had lived very different lives.

While many of them had grown up on the lakefront or in the affluence of Cumberland, Maryland’s “Queen City” down off the mountain, my colleague and I understood the consequences of these decisions far more than those who had, fortunately, escaped the same lived experiences.

Shelley Argabrite, with whom I completed this project, and I had experienced an array of these consequences, risk factors, and social determinants of health that continue to shape how we approach our work in public health and everyday life.

In fact, we’ve become best friends over the years. Trying to make meaningful change in public health is the adventure of a lifetime, and I can’t imagine a better friend and “partner in progress” with whom to take on impossible challenges. We’ve driven this work together, and everything you see is the result of “we,” not of me.

Photo: My friend and “partner in progress” Shelley Argabrite.

At the end of this meeting, we moved forward with policies that put paperwork before people, and because of that, I often wonder about those who wouldn’t have gone hungry if I had been more vocal, more willing to assume the risk on my career, or more willing do this then, despite the insurmountable barriers.

I told myself that “I’m a systems person, not a program person.” My public health wizardry consists of reports, data, informatics, oversight, performance management, quality improvement, strategic planning, and other words that, while important, pale in comparison to addressing actual problems right in front of us. Over the years, I’ve longed for more. To make a difference, to impact people where they are, and to better understand the programs (and overarching systems) that impact real people – or, as Evan says, “Mess with people’s lives.” In this program, those words have taken on an entirely different meaning. Through expansive exposure to new ideas, better evidence, and brilliant friends across the RHI (Rural Health Innovation) cohort, I’ve found a whole new way of working.

Growing up in Appalachia, I’m no stranger to rolling up my sleeves and getting my hands dirty. Whether it was catching crayfish in the crick or pulling coal out of an open seam in a ditch and pretending we’ve struck gold, my childhood was defined by hands-on activities. Throughout my life, I was told to get better at “computers,” going to the Ruth Enlow Library to learn how to build websites and code (all too often promised as the pathway out of Appalachia), and over time, I became more comfortable staying at an arm’s distance. This experience changed that along every step of the journey. I remembered not only my own lived experiences, but who I am outside of all the voices telling me to run if I’m ever given the chance.

Throughout the years that followed, we wrote and received small planning grants for diabetes prevention and management, expanding SNAP access for farmers, and other food security-related topics. However, most of these never resulted in more food in hungry bellies. While this work was important in its own right, I often questioned whether it was perceived as performative by those who truly needed help from a system that is often better designed to keep them where they are, rather than help them move forward with their goals, dreams, and aspirations. I’ve learned a lot about QALYs and other measures throughout this program, but I’ve wondered whether many of those publishing this research really understand what quality of life looks like here: not just wealth, but more often food, warmth in harsh winters, time with family, and a little joy sprinkled in the mix.

When the opportunity arose during my first year at Berkeley to write a grant for the food bank that everyone told us would/could never exist here, Shelley and I took a leap of faith and hoped that we’d figure it out as we went.

We’ve written and received many grants, but this would be the first at this scale as a hands-on program. As a Health Planner/Strategist (Shelley) and an Informatics Administrator (me), running what amounted to an almost entirely new agency was an unprecedented undertaking.

Along this journey, we found others who shared our vision for a community center that not only addressed food as a social determinant of health but also built community and shared resilience.

Modeled after short-term programs of the past that came and went, and those that were already successful, but limited in funding and resources, we sat out with CBPR (Community-Based Participatory Research) methods in mind. Rather than build a program for – or even with our community, we wanted instead to help our community build a program of their own.

While the application was framed around our experiences, including my own packing Brown Bag boxes in the basement of the American Legion during summers as a child for a box of food (paid for with labor, instead of cash), we decided that it should be representative of what people needed, rather than what we thought they needed or what we thought we heard from them directly.

While admittedly, this at times felt like a mistake, as angry emails flooded our inboxes after community sessions when one or two of the folks attending felt slighted by the direction the project took, I am grateful that we followed this path, given the outcomes that we’ve seen nearly a year later and those vocal voices that later became key partners. After all, we’re all in this together in Garrett County.

Despite these challenges, the partnerships formed through this work have not only been wildly successful but have also reverberated through programs and systems affecting multiple health outcomes.

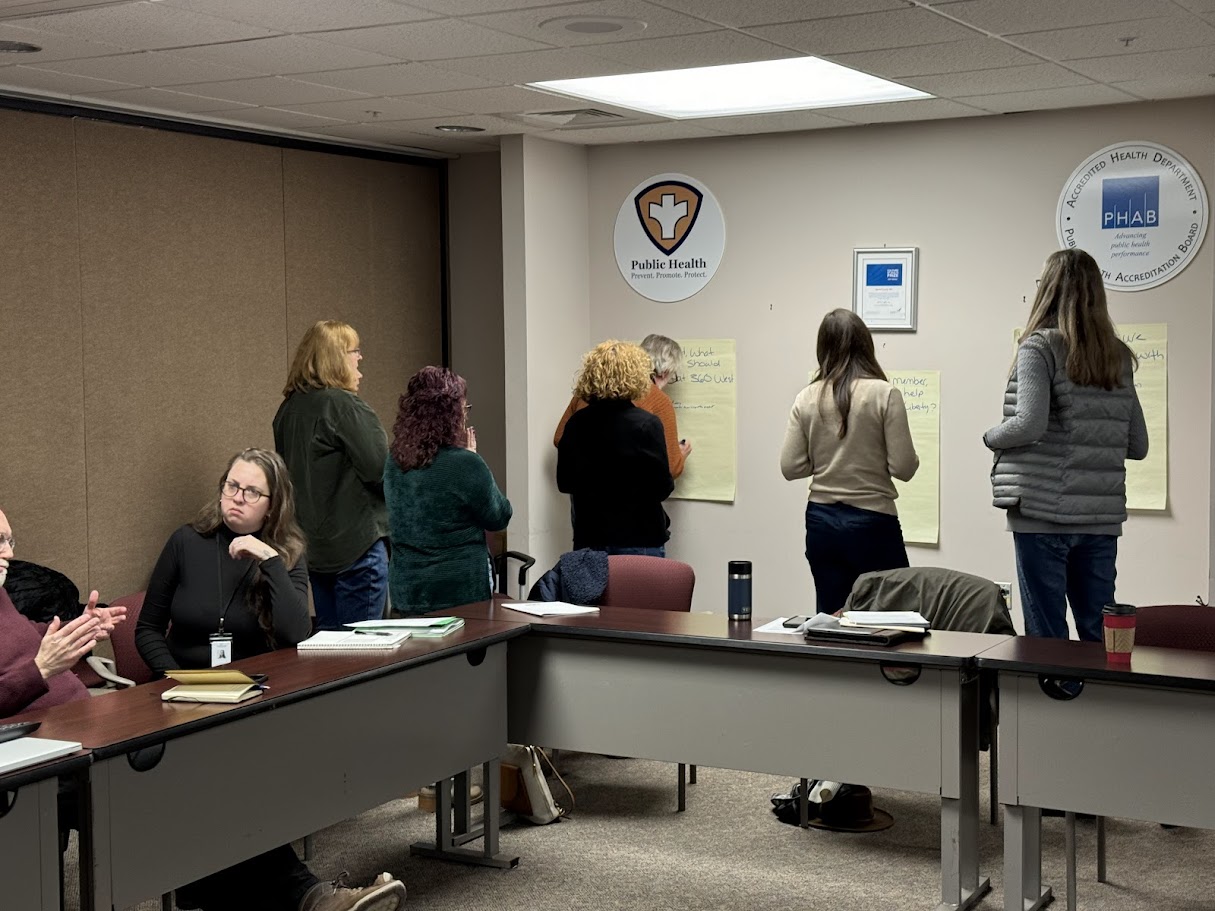

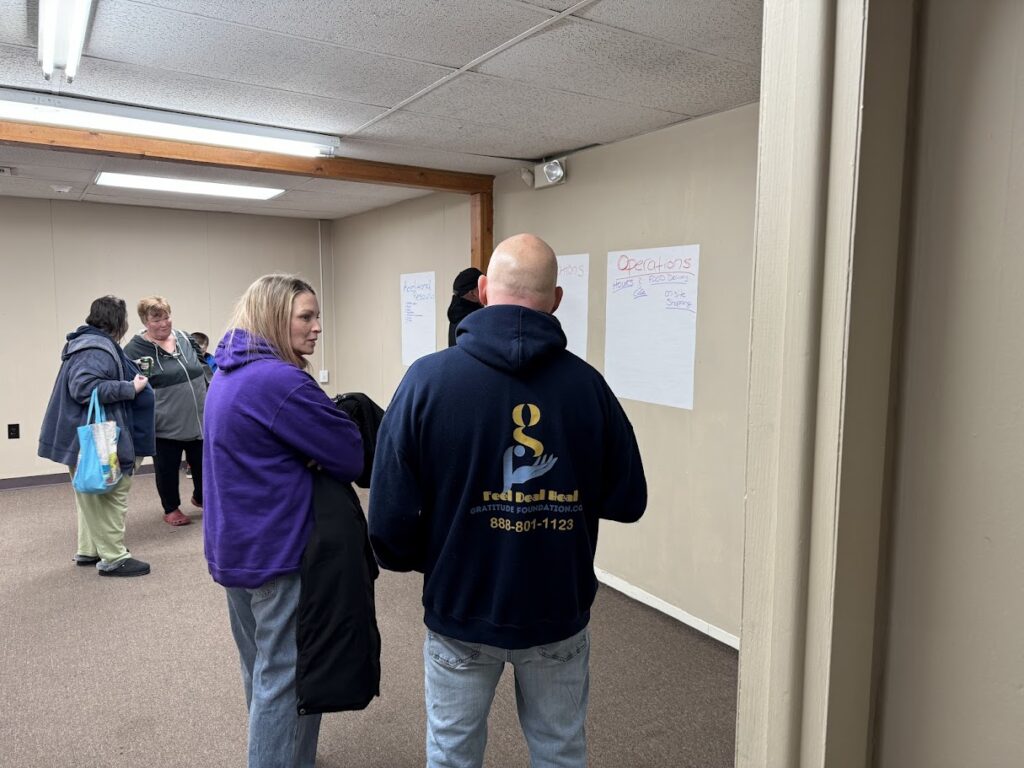

Photo: A community planning session in the same conference room where decisions were made at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

![Photo: This session, the same as shown above, was held during a blizzard. Many folks participated virtually, which also enabled participation by those in remote communities [where CHNA sessions were held in-person], given the large geographic size of our county.](https://mphinaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IMG_1122.jpg)

Photo: This session, the same as shown above, was held during a blizzard. Many folks attended virtually, which also enabled participation by those in remote communities [where CHNA sessions were held in-person], given the large geographic size of our county.

Notably, our partnership with Maryland Physicians Care enables reimbursement and sustainability for their Medicaid clients (92% of the market share in Garrett County), and helps sustain the work of Garrett County Community Action in expanding programs related to other social determinants of health at the food bank.

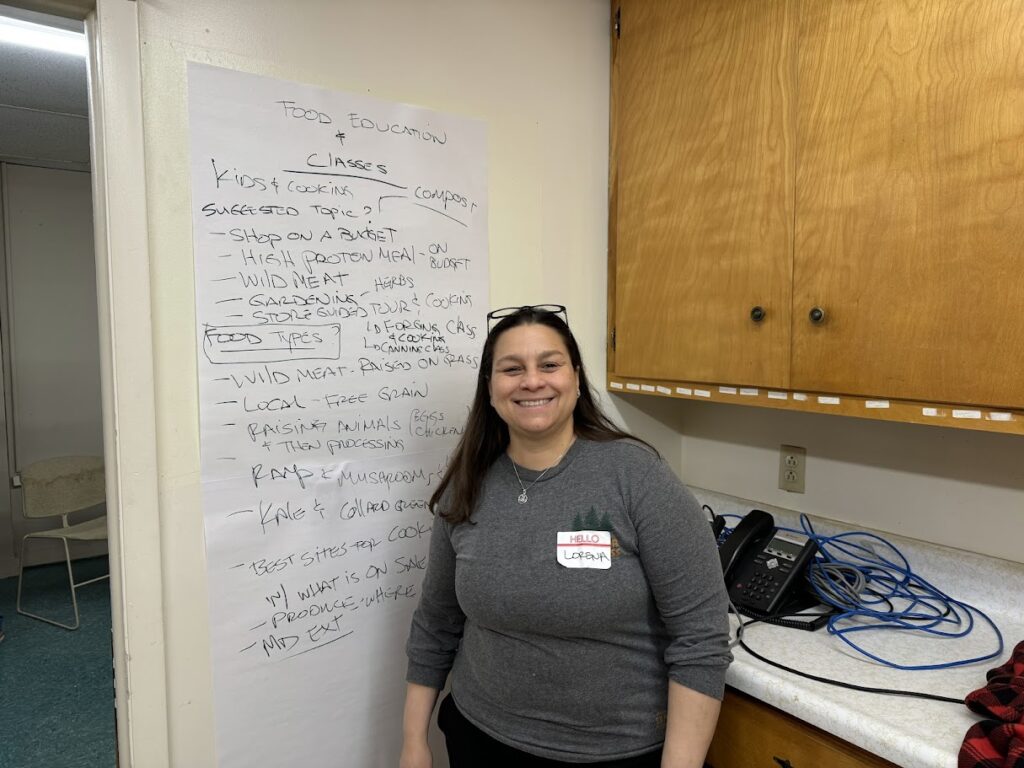

When I first met Lorena de Leon (Maryland Physicians Care), I knew I found a changemaker – someone who would stop at nothing to make people’s lives better. Her vision, based on experiences and work completed throughout many diverse communities with similar struggles around poverty and the compounding impacts of social determinants, shaped this work greatly – showing us what was possible to further extend the model. Our tour of Maryland forever changed my own view of what’s possible.

In my job, I am a Public Information Officer (PIO), epidemiologist, health planner, programmer, informatics and HIE (Health Information Exchange) administrator, and wear a variety of other hats. I rarely go anywhere not prescribed by a funder or in search of the next funding source to move systems further. Yet, Lorena convinced our team and Chris Mullett (Garrett County Community Action) to take another leap of faith and tour her favorite food-centered projects throughout Maryland.

This trip showed me incredible models, from CAN’s client-choice free supermarket (https://www.canconnects.org/food-pantry) to the Food Project’s impact in Maryland’s poorest zip code (https://uempowerofmd.org/the-food-project), in the heart of Baltimore’s struggles. I met people with incredibly different lived experiences, and I am far better off as a person for seeing how they’ve willed change into being from sheer determination and united purpose. Many of these folks, while different from me in almost every way, were doing the same kind of work: building a better future for their friends, family, and neighbors.

Photo: One of our site visits to The Food Project in Baltimore to learn more about building food security infrastructure programs in rural Garrett County, Maryland.

These models incorporated commercial kitchens, childcare, MVA representatives (for driver’s licenses and learner’s permits), small business incubators and workforce programs that offered actual opportunities to move above the poverty line (https://www.seedynutty.com/), harm reduction, and are aspiring to offer more programs that continue to create jobs and improve health outcomes (like the upcoming doula program in Baltimore City).

Passing back through Sideling Hill, where locals say Western Maryland and Appalachia really begin (rather than the maps produced downstate), we excitedly shared a joyful moment – not only of our return home after a long journey, but on reflecting on the new friends that we’ve made and continue to learn from.

Then the hard work really began.

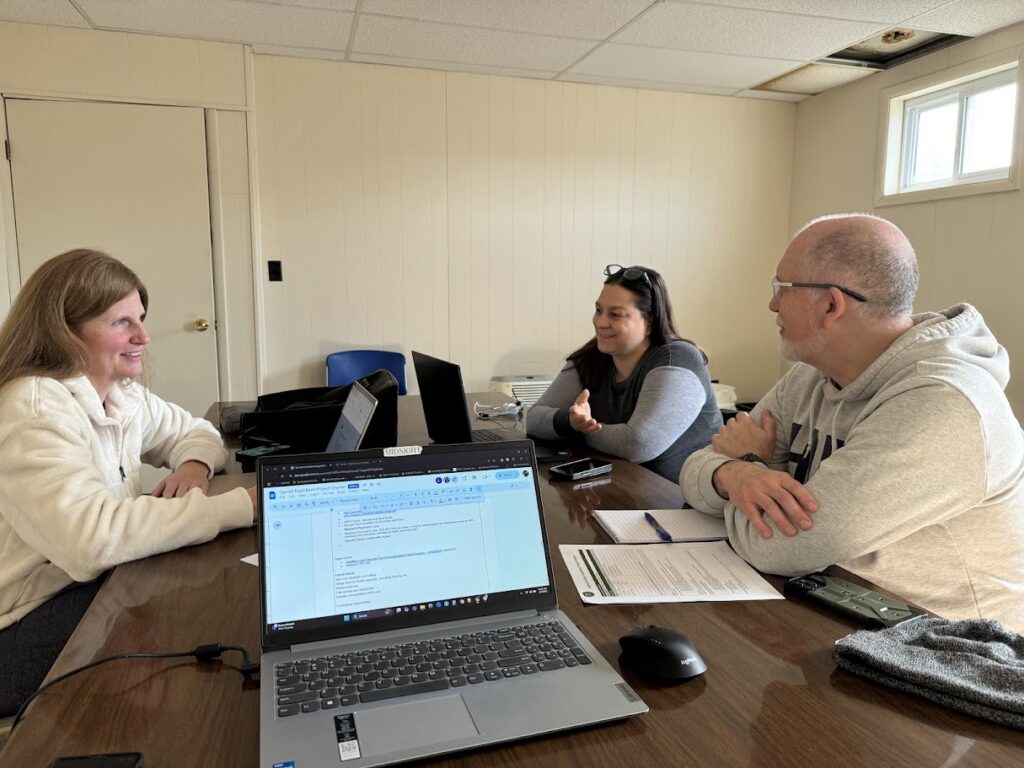

Photos: Our first day exploring the physical space at 360 West Liberty Street (Lorena, Chris, and Shelley + me behind the camera).

A few months earlier…

“We got the grant!” our team shouted excitedly in front of an almost entirely new Management Team, five years after the weathering days of the pandemic, where this journey began.

Oh boy – how were we actually going to do this with everything else we had to do in our already over-encumbered roles?

Partners.

Photo: Shelley and I after a community event in Bloomington (a remote Garrett County community near the old Luke papermill being torn down), serving folks with Healthy Together and the Judy Center while interviewing participants about how 360 Access Hub could help them (approximately 40-45 minutes away from 360 Access Hub by car).

Photo: A few weeks later, unprecedented flooding hit 4 miles down the road in Westernport, further exacerbating issues related to housing, employment, food security, and other social determinants of health. Lorena, our collaborator, was a major flood recovery partner. (Photo from Accuweather)

Photo: Me with friends from Healthy Together (AHEC West), the Judy Center, and Recovery Coach Jenny Hesse in Kitzmiller (a historic coal town across from Elk Garden, WV, over the North Branch of the Potomac River). This photo was taken in the old school building, which now houses a Head Start class and a small branch of the Ruth Enlow Library.

Those same folks we took that journey with continued to show up and deliver on this vision of something we knew we needed, but we weren’t quite sure how to achieve.

Despite many public meetings before and after the award announcement, and the exploratory journey shortly after the award notification, there was a mountain of work standing between us and where we are today (still only about 50% of the way to where we want to go).

How were we going to get a grip on this project and frame our community’s vision with the unprecedented award from CareFirst, one of our best funding partners in Western Maryland? There were shared goals, but different process measures in actualizing these visions.

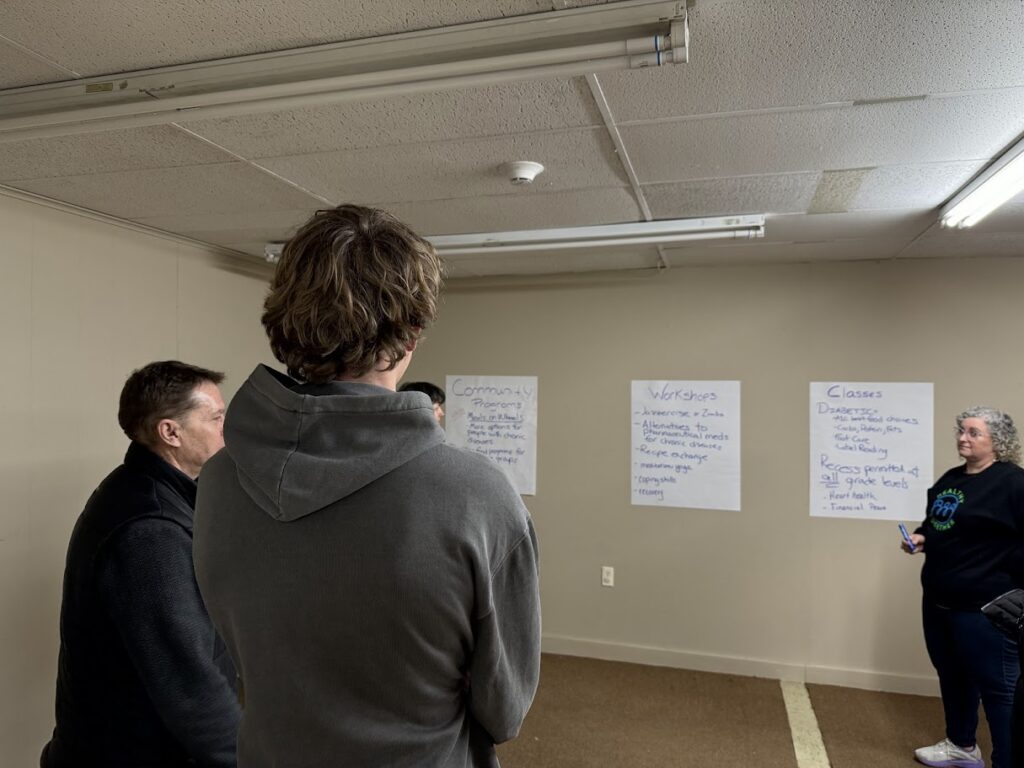

Photos: Our first open house and first community visioning session in the space.

(Only participants who consented to photos and stayed after are shown.)

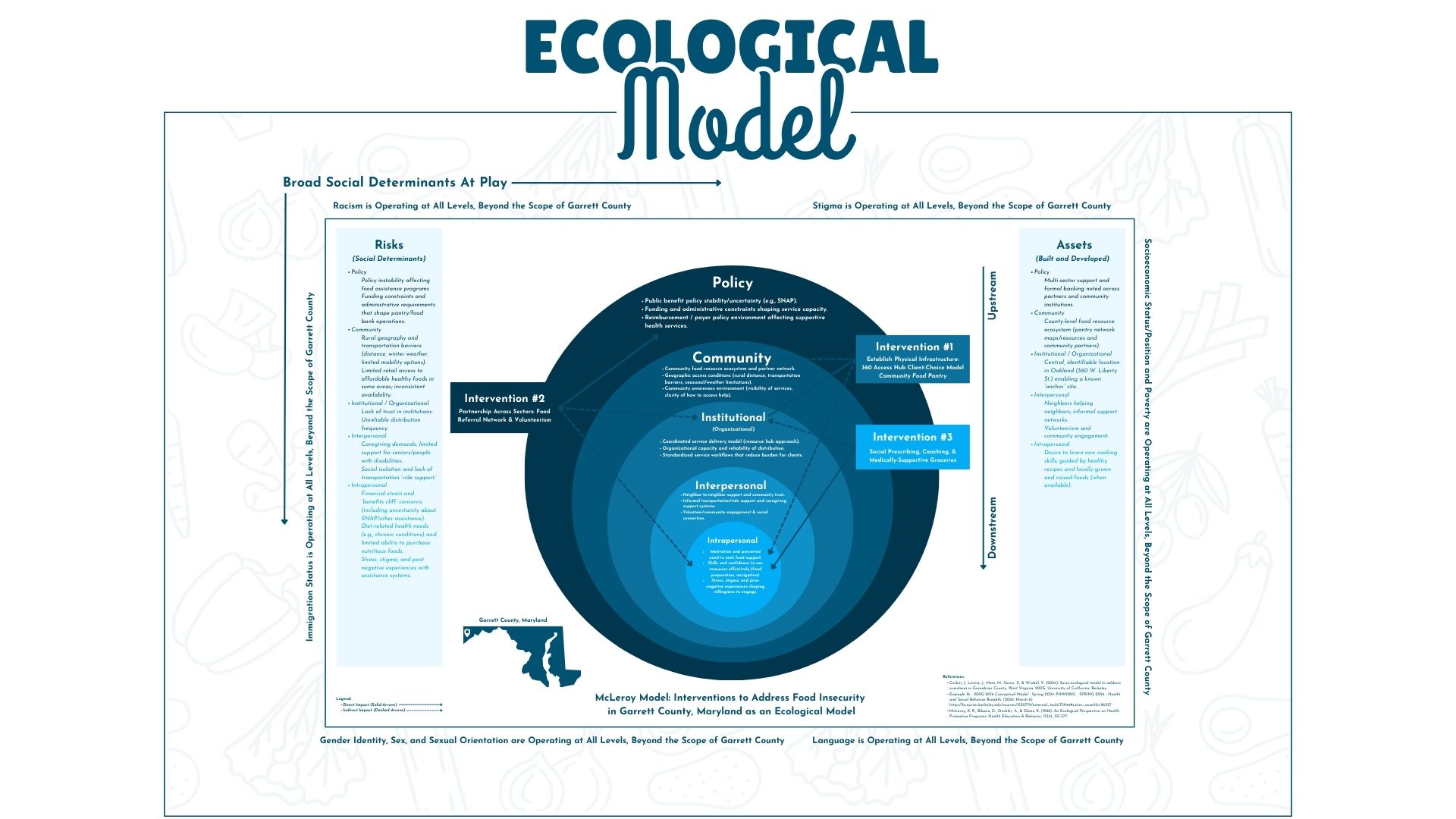

“Socio-Ecological Model,” I recalled, thinking WWED (What Would Evan Do?).

We had the research, the community vision, the funding award, and the partners, but how exactly do you form a new agency that is still kind of part of a bunch of different organizations with different mandates, policy requirements, and prescriptive rules?

As I soon learned, it’s even harder to construct a socio-ecological model with even more people – especially those with articles and specifications in the Annotated Code of Maryland. I dare to even think of the hours it took to make this simple diagram, refined by group after group. While less perfect and more practical than the academic models shared by others in the course, this model helped us align work across agencies, community-based organizations, and as individuals.

Further, we coupled this with discussions framed around Bardach’s Eightfold Path using strategies imparted from Irina’s Healthy Policy Methods course. This, along with the accompanying strategies from the course, proved invaluable in advancing complex work with multi-sectoral partners.

Through this work, we discovered that Community Action had the space (later becoming a key partner) – the old cinderblock Garrett County Community Action building at 360 West Liberty Street that had sat empty after the planned use as an emergency homeless shelter for unhoused persons fell through, as so many projects before. Now located in an old school, Community Action graciously offered this space (greatly in need of some TLC) with the hope that this project would come to fruition.

The address, coupled with the number one theme from our Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) – Access to Care – and followed by other social determinants, gave us a name almost immediately: 360 Access Hub (https://360accesshub.com/).

Photo: Food system sustainability and resiliency came up often in listening sessions. As a result, we also explored aspects of victory gardens for 360 Access Hub. These kits (shown above) were provided with online education at the Garrett County Rec Fair at Deep Creek Lake State Park while we continued to prepare the physical space. Program participants were also able to get a food voucher to Casselman Market to address immediate needs. My new friend, Samantha (shown center), helped drive people to this event and others as we addressed needs prior to the opening of 360 Access Hub.

Throughout this practicum project, I noticed something that had changed in me, shaped by my experiences at Berkeley: I found my voice.

When I began this program, I promised myself that I would be more outspoken, less afraid to take up space, and more proud of the person I am (something I often struggle with, given my upbringing). No longer othered, instead outspoken. I found confidence in this program to be a changemaker, to be bold when others go silent, and to also know when to sit back down and let others take up space. In its own right, this has been a transformation that I never expected would flow back to my life in Appalachia – no longer in the comfort of an online cohort, but back here with people who’ve known me my whole life as someone else.

Photo: Me being slightly less uncomfortable on this side of the camera.

Over a few months, through construction projects (primarily carried out by incredible volunteers from Community Works [“C” Works] Garrett County [https://www.facebook.com/CWorksGC/]), process measures that included the development of evidence-based tools to address food security in collaboration with folks from Johns Hopkins, American University, and our incredible friends at CareFirst, and the complexities of running a center with perishable foods, we found time flying by in anticipation of our ribbon cutting event.

Photo: “C” Works volunteers continue to show up to help neighbors.

While we’d hoped that folks from the community sessions would come, many of them lacked transportation (another program element that began to come online in January of 2026) and other types of access, despite our best efforts to carpool (coordinated mostly by Shelley’s teenagers) and utilize the extremely limited public transportation available (Garrett Transit Mini-Bus).

There were an awful lot of happy tears at this event, and the community response was standing-room-only by the end of the evening, as folks kept leaving to bring back others from sessions they’d attended and people they knew in need (who later that night became the first people served at 360).

Video: My uncomfortable moment in front of the large group gathered at the ribbon-cutting event.

Photos: Pictured below are photos from the event, including our INCREDIBLE friends and funders at CareFirst.

That night, Garrett County knew that something novel had been created here – by us and for us. Together, we’d actually built infrastructure – something that felt like it hadn’t been done since we started tearing down schools in the late 90s, as our manufacturing and energy-based economy collapsed and our population swiftly declined.

While there were constantly “nice things” happening at Deep Creek Lake, centrally located in our county, these were often for “them” rather than for “us,” as we often heard at listening sessions and in the completion of our larger CHNA.

Perhaps it’s the wealth inequality between the multi-million-dollar lakefront mansions and the houses three miles away with packed-dirt floors next to Swallow Falls State Park that creates this crevice within our community. Or the built infrastructure that is seemingly erected without hesitation to serve tourists and second-home owners, including popular glass construction methods (for those incredible lake views) that cost more than our food bank’s operating budget in heating alone in one of the snowiest places East of the Mississippi River. Nevertheless, it is rarely us and them, and far too often them instead of us.

That night, people felt like we had done the impossible, and I like to think this is the first of many great things to come in a new era of Appalachian grit and willpower, creating things for future generations of folks in Garrett County, as so many of those did before us.

Photo: Farmers, like Katharine Dubansky from Backbone Food Farm (https://backbonefarm.com/), are a major part of our solution to food insecurity. Locally-grown produce centered around meals, rather than ingredients, helps participants eat healthier while supporting local economies.

Photo: Shelley and Christen pack bags while I try to get them to participate in photos. 🤣

Months later, we’ve served hundreds of households and thousands of stakeholders, including those in neighboring counties and across states. The need is higher than ever, given the challenges posed by external forces and policymaking.

Despite these odds, we’re collaborating even better month-after-month, incorporating more and more services, from the Department of Social Services (SNAP enrollment) and Community Action (child care enrollment and heating assistance) to the Local Management Board (jobs, wages, and economic development) and AHEC West (harm reduction).

While my practicum propelled this project in unique ways, the work has just begun. Tomorrow is another day, and folks deserve neighbors who take care of them like they’re family – as they often are in Appalachia.

This MPH program and practicum will forever be a piece of me and all of the lives it has already and will continue to impact across Appalachia.

Throughout this journey, I have connected with countless changemakers and people willing to give a hand – whether they’re native to Garrett County or not. These connections are establishing future funding, will help us serve more people across borders – particularly in West Virginia, and inspire folks to keep going. There’s a long way left to go, and housing is next. 😉

Photos: Pictured below are photos from a wreathmaking cross-over event, showcasing 360 Access Hub as more than a food bank – we’re a community center for the tough times and the good times.

From our holler to your house, I want to thank everyone who reads this and has influenced this journey. You are making a difference – right here, every single day.

Photo: The current 360 Access Hub team from the Garrett County Health Department: Shelley, me, Christen, and Suz!

Leave a Reply